Holograms VR AR and the Future of Reality

After decades of false starts, holographic displays are finally coming to market. These new holographic devices go by many names — holographic interfaces, light field displays, superstereoscopic displays, volumetric displays — but as a group they are fundamentally different than the VR and AR systems you’ve heard about before, simply and powerfully because these holographic displays don’t require headsets. Groups of people can now interact with virtual characters and worlds without the friction of gearing up, delivering on the promise of a holographic future long promised in science fiction. Nearly every industry — medical imaging, communication, 3D design, advertising, the memories industry, entertainment, drug design, education—will be transformed by this shift over the coming few years.

Holographic displays serve as the third pillar next to the VR and AR systems you’re probably more familiar with, together bridging the real world and 3D digital space. Here’s a brief summary of how these systems differ from one another, followed by some additional detail on the new players in the emergent field of holographic display.

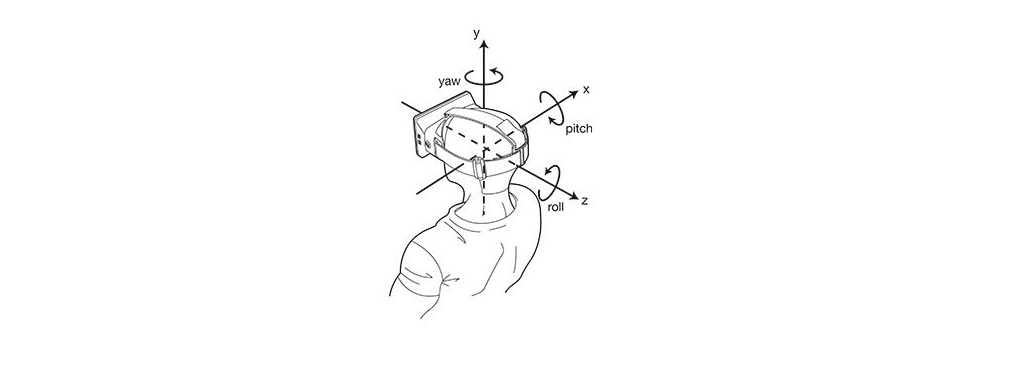

Virtual Reality (VR): Gear up, leave the real world, and enter hyperspace. Akin to scuba-diving — powerful and highly immersive, but for the most part an experience that people will dive into only occasionally because of the friction of putting on VR headgear.

In fiction: Lawnmower Man, Ready Player One, Black Mirror: Striking Vipers

In reality: Oculus Quest, HTC Vive, PSVR

Augmented Reality (AR): Put on a set of special glasses or goggles and see a digital overlay on the real world. If VR is like scuba-diving, AR is like snorkeling, half-way between two worlds, in this case between the real world and hyperspace. Still requires gearing up for the most part.

An avalanche of acronyms and terms have flowed into this field — Augmented Reality (AR), Mixed Reality (MR), Immersive Computing—and the list seems to be growing every day. But for old school dudes like me, AR is the banner flying above these subcategories, covering any technology that puts a digital overlay on the real world.

AR comes in many different flavors, including the most advanced forms with three-dimensional overlays that sense and interact with the real world (3D headset-based AR: Hololens 2, Magic Leap One, the Tilt Five system), two-dimensional glasses-based overlays (2D headset-based AR: RealWear, Google Glass 2, Focals), and two-dimensional tablet and phone based overlays running well-known apps like IKEA Place and Pokémon GO (Mobile AR: iPhone X, Google Pixel powered by ARKit and ARCore).

In fiction: Hyper-Reality, Robocop

In reality: 3D headset-based AR: Hololens 2, Magic Leap One, Tilt Five; 2D headset-based AR: RealWear, Google Glass 2, Focals; Mobile AR: iPhone X, Google Pixel powered by ARKit and ARCore

Holographic Display: As VR is to scuba-diving and AR is to snorkeling, holographic display is more like having a vast aquarium in your living room where a group of people can peer into another world together without the friction of putting on any gear whatsoever. Holographic displays give groups of people the ability to gather around a dynamic virtual world represented by a field of light — in this case without needing to put on a headset.

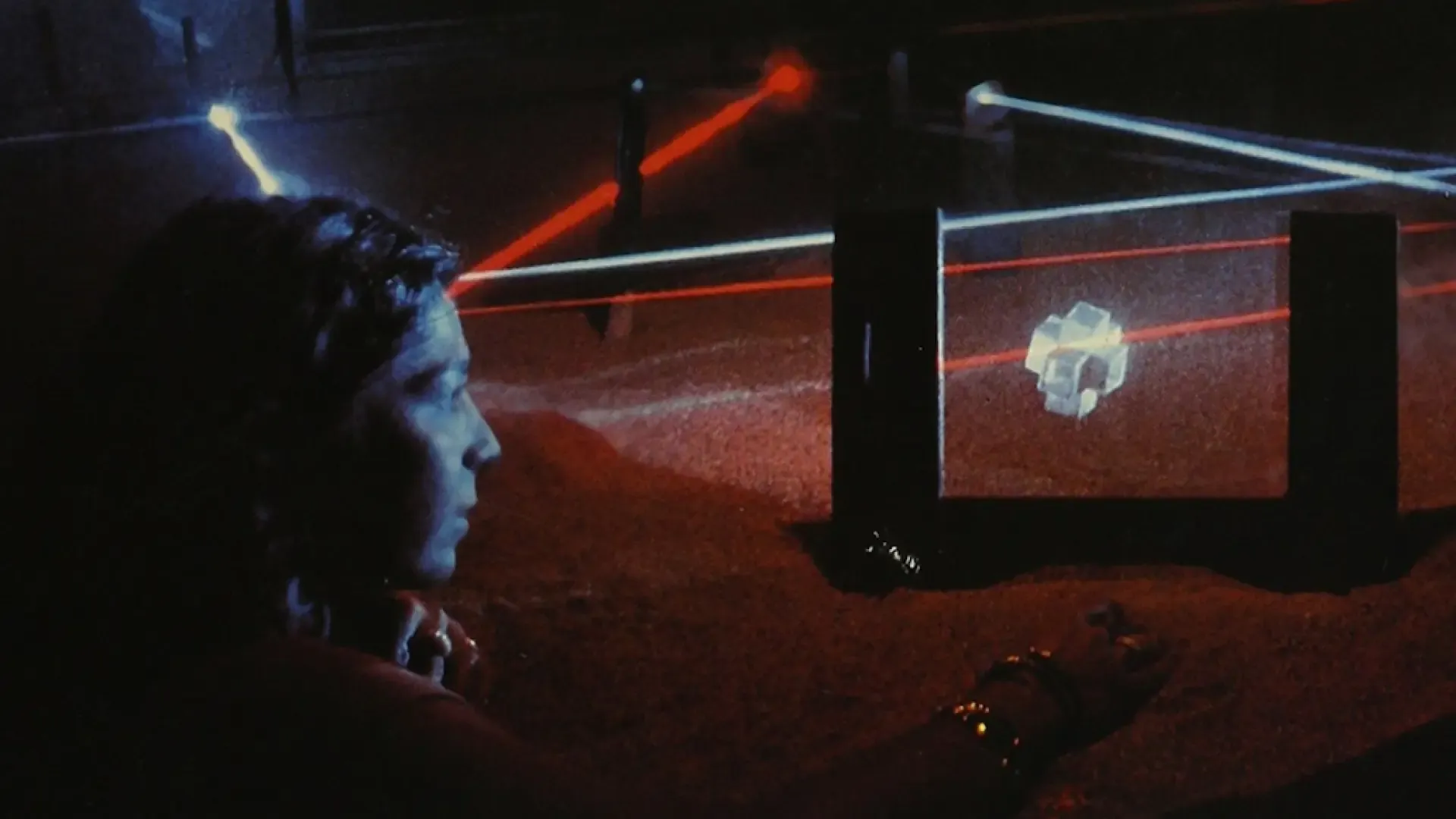

In fiction: Lots. Favorites include holograms in Back to the Future 2, Blade Runner 2049, Her, Minority Report, Paycheck, Big Hero 6, The Expanse, Iron Man, basically every Marvel movie, and of course Star Wars.

In reality: Looking Glass, Avalon Holographics, Light Field Labs, Leia Inc, Voxon

As is the case with AR, what groups call a “holographic display” covers a broad spectrum of technologies, some more advanced and powerful than others and each serving different needs. Here’s a bit more detail on the main sub-categories in the holographic arena:

Superstereoscopic Displays, also known as Super Multi-view or Light Field Displays: Arguably the most versatile systems within the holographic category, these present a myriad of genuinely three-dimensional perspectives to groups of people through a dynamically-generated synthetic light field (examples:

Looking Glass, Leia Inc, FOVI3D, Light Field Labs, Avalon Holographics). Typically no moving parts, headgear, or tracking are needed.

These displays work by emitting a vast quantity of light rays with careful attention paid to the direction of those rays. Where a traditional two-dimensional computer monitor might present a single view or perspective of a scene, a superstereoscopic or light field monitor can present dozens or hundreds of perspectives of that same scene simultaneously.

This approach has the ability to represent anything real or digital (objects, people, etc.) with extremely high three-dimensional fidelity, but at a price. Because of the vast amount of data involved in pulling this off, tremendous computational power and very high pixel densities are typically needed. These requirements are part of the reason that this technology is only now beginning to come to market.

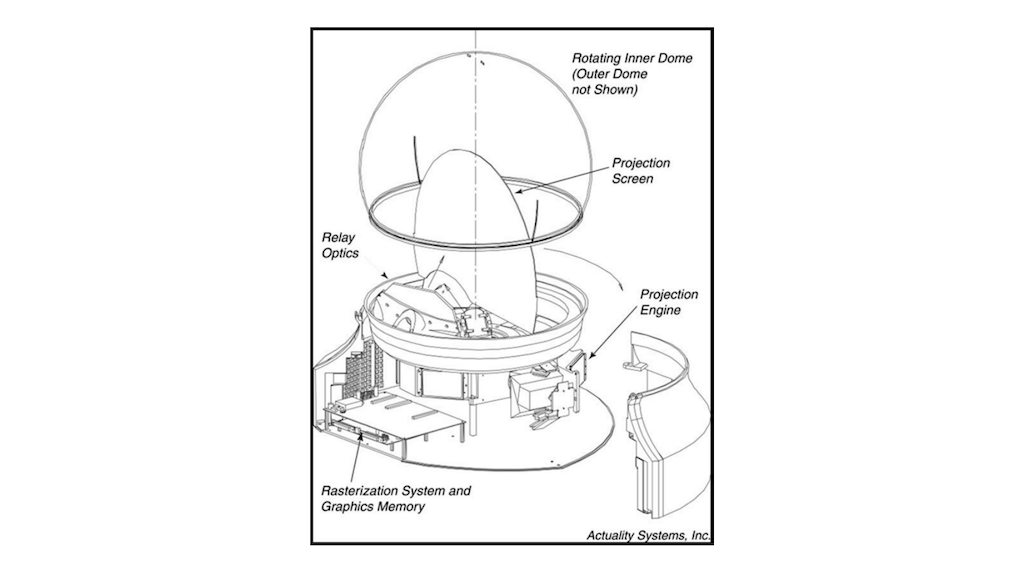

Swept-volume volumetric displays: Another popular sub-category under the broad banner of holographic is the swept-volume volumetric display (example: Voxon), in which light is scattered off of a physical medium, typically an oscillating plate or helix. This type of system was a leading contender for the ultimate general purpose three-dimensional interface a couple decades back, but the need for a moving part that sweeps the entire viewable volume has limited its reach thus far.

2D pseudo-holograms: The most-Youtube-famous type of display under the broad banner of hologram, this category includes rapidly rotating two-dimensional LED fan systems (HYPERVSN), and two-dimensional reflections aka the Pepper’s Ghost illusion (the well-known Tupac performance, VNTANA). These systems are often used in advertising and entertainment applications, particularly where viewers are over 30 feet or more away (since our stereoscopic perception drops off around this point, the fact that these displays are two-dimensional doesn’t matter if the audience is at a distance).

Holography in the technical sense of the term (the art of capturing laser interference patterns on holographic film) isn’t discussed much these days. That medium, while wondrous in many ways, isn’t dynamic and rarely full color. The cultural definition of a hologram as espoused in the movies and the technologies described above has entirely taken over.

In my next post I’ll go into how holographic displays are taking the path that desktop computing took in the late 1970s, starting with a group of engaged/fanatic developers, then moving into the first enterprise applications, and ending at last with holographic displays in homes around the world.

Inspired by movies in the 80’s and 90’s, the author Shawn Frayne has been reaching towards the dream of the hologram for over 20 years. Shawn got his start with a classic laser interference pattern holographic studio he built in high school, followed by training in advanced holographic film techniques under holography pioneer Steve Benton at MIT. Shawn currently works between Brooklyn and Hong Kong where he serves as co-founder and CEO of Looking Glass Factory.